One aspect of India that can’t be ignored, whether one comes seeking it or not, is the prevalence of something spiritual. Spending most of my time in Rajasthan, I didn’t expect to encounter much of it, or spend time investigating the practices that bring so many Westerners to this part of the world, but still, it remained inescapable. It is inherent in the streets: in the countless temples and statues, the roaming cows, and even in tiles of deities on alley walls to deter urinators (yes, that’s a thing). I wanted to learn more about Hindu, a religion and culture I knew little about before coming to India. I’ve come away with something since, I think, though there’s a universe still to learn.

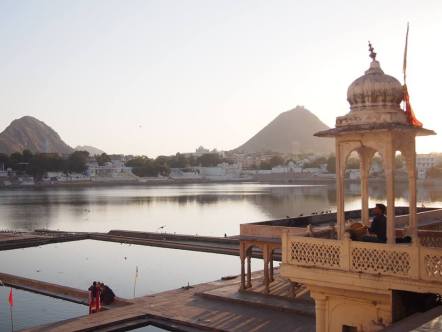

In Pushkar, a Brahmin led us to the ghats on the sacred lake, not far from where Ghandi’s ashes were spread, for the flower ceremony. It was much quieter by the lake than I expected, a trickle of Israeli hippies, middle-aged tourists, and beggar women and their children. This is the lake where Brahma is said to have dropped a lotus flower, both giving the lake its name and its proximity to the only Brahma temple in India. Bodies are brought here, as they are in Varanasi, for cremation. The holy water is said to remove bad karma before death, and to bathe in the water can cleanse the soul. As Westerners, we would have a simple ceremony for peace and prosperity, administered by a trustworthy Brahmin (for scam ceremonies are prevalent on the ghats). We each had a plate with powder, a coconut and flower, and, seated with our eyes closed, we repeated the blessings in both Hindi and English. We received our bindis, and laid our flowers on the water. It was so still and peaceful, it was difficult not to feel something of the significance. Later, as the sun set over the lake, I watched a cow trundle beside a pair of men in full white robes as a man played a drum across the water and felt a very particular kind of peace. It wasn’t by any means the typical kind of spiritual experience people come to India, to places like Pushkar, to find, but it was there, with something very organic about it.

Varanasi, like Pushkar draws pilgrims to water. The first thing I saw when we arrived at the Holy Ganga, taking slow steps down to the ghats as a hint of sunrise blurred black to grey, were cremation fires burning. Then there was a body in a white shroud, slender-shoulders and a little dent of a nose giving human shape to the white on the flames. I tried not to stare, but it was too difficult not to. Men stood around fanning the flames, some with bald, cleanly shaven heads and faces, a marker of close family of the deceased. They played upbeat music from a rattling speaker and so it didn’t seem at all the kind of mourning I’d expected. We watched the sunrise from a rowboat, passing men bathing, washing laundry, performing their own small and private rituals. Everything happens here. Later, as we ate lassi in a tiny shop on a tinier alley, we watched procession after procession of brightly coloured mourners pass us by. They carried prone bodies, wrapped in oranges and yellows and adorned in marigolds, as they sang. There were two that came by with a band of drummers. This, Abhi told us, was because they’d lived to be more than one hundred. The second came by as we left the lassi shop, and I pressed myself against the ancient wall to be out of the way. The face, this time, was not covered in a shroud. Sunken cheeked and paled, suddenly it felt different. I’d seen many bodies by then — those passing in the streets, or on the ghats as we’d walked by during the day. We stopped and watched, from a respectful distance, as men prepared a body for the flames. They sprinkled oils and dustings of something on the shroud, then let the flames build. Stacks and stacks of logs act as walls around the burning areas, and goats and dogs clamber among them. The bodies burn for three to four hours before the remains are given to the river. Sometimes this can include parts still intact: the broad shoulders of men, the hips of women. And then, just meters from where these rituals take place, men bathe themselves. One of the cremators, a man whose family have kept alive the holy flames for generations, told us that there are those who fish in the waters for trinkets of the dead, as jewellery remains on the bodies. They sell these, or so they claim, to pay for the funerals of the poor.

But it’s not all death on the Ganges. At dusk, after our lassis we took another boat out to watch the famous Ganga Arti ceremony on the Dasaswamedh Ghat. I’d been waiting for this ceremony for three weeks: it was one of the things I was most looking forward to seeing on the trip. My expectations were high, and luckily for me, they were met. Before we joined what seemed like hundreds of boats swarming the waters, packed in tight to a view the ritual, we stayed where it was quiet. We were given a flower and candle, and after a brief and silent prayer, let them adrift on the waters. It was magical, the lights flickering as they drifted further and further from us. Other boats did the same, so at points it seemed like the whole river was lit with tiny pinpricks of yellow. Once we’d found our place among the crowds, we watched the Brahmins perform the ceremony. There was the rattle of bells, among deep voiced chants as incense plumes carried high into the air. I sat back with that same sense of peace, despite all the voices around me, tourists on the boats, and became entranced.

We watched the same ceremony days later in Rishikesh on the foothills of the Himalayas. Far from the crowds and bustle of Varanasi, where the Ganges water ran blue-green and clean, the ritual was very different. We sat close amongst the crowd as the robed children and young men studying Vedas at the Parmarth Niketan stand in two rows, led by a greying old man in white, and a long-haired man in orange, singing for an hour. We were surrounded by a mix of Indian locals and tourists and pilgrims, as well as the Westerners and hippies who come to Rishikesh to study yoga practice. Everyone sang together, even myself, by the end, unable to keep myself from falling into it. As the sun set, the lamps were lit and carried down to the water. People scrambled for a turn to hold them, to swing them in wide circles before them, before passing them to the next person to take down to the water. I watched at first, feeling like a strange observer of it all, but then an Indian man made eye-contact with me and, holding out the lamp, ushered me toward him. It was as though the crowd parted for me, and there was no more jostling as I reached for it. But I was self-conscious, and my circles were barely trembles, and I was relieved when a man in white took it from me and went down to the water. But still, I felt honoured, like I was chosen or something — silly as it sounds. It was so much more of an intimate experience than in Varanasi, and I’m so glad we went (as we were both getting quite sick by this point). Afterwards, we sat on the steps of the ghat, watching children let their flowers and candles float down the river. It was another moment of peace, and couldn’t help but feel quite taken by the place.

I decided that I’d need to come back to Rishikesh again. It was a shame I was so sick while we were there. We didn’t get to take a yoga class, a must-do in the yoga capital of the world, or hike the mountains, or visit the waterfalls or mountain temples. Instead, we walked slowly through the streets, past ashram upon ashram. There was a much slower pace to Rishikesh, and I felt so much relief after having been back in Delhi the day before. In the morning, we sought out the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi ashram where the Beatles stayed when they came to India. It was hidden in the outskirts of the city, amongst tall monkey-filled trees in the national park. There were no signs to indicate an ashram — unusual in a town literally plastered with ads for ashrams and yoga schools — and instead a giant sign for a tiger reserve greeted us. As it turns out, the ashram is now preserved as a nature reserve, and is overrun with crawling vines and drooping trees. We wandered through the abandoned buildings, many of them graffitied with Beatles lyrics and images. There are hundreds of tiny ‘caves’, small, round huts where people once lived. The Beatles occupied number 9 (it all makes sense!), and it was quite an experience to sit in the tiny space and hear the echoes of our voices, surrounded by psychedelic Beatles graffiti. This is the type of spirituality that Rishikesh is known for. The Ganges remain holy to the locals in the same way they are at Varanasi and Haridwar, a pretty town we’d stopped in briefly on route to Rishikesh. But Westerners come here for the reasons that drew the Beatles. To find something of an experience, to practice and devote themselves to yoga, to seek enlightenment. I quite like the idea of doing the same one day – as cliché as it may be.